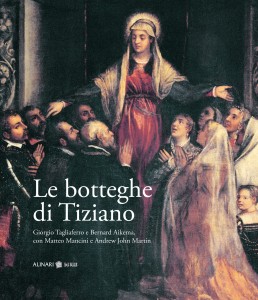

Le botteghe di Tiziano (Titian’s ateliers)

Free delivery in Italy, payment on delivery abroad

The study of Titian’s correspondence has engaged Lionello Puppi for years. He has researched the documents in various European countries as well as re-ordering of the Titian archive preserved in the Magnifica Comunità di Cadore. Since last summer, three collaborators have worked alongside Puppi, transcribing the letters and creating the relevant onomastic and topographical indexes, which are quick and easy to consult. They have worked with archives, museums, libraries and the private owners of Titian’s letters. Valuable material was collected, with the aim of acquiring a passageway into our knowledge of Titan’s life and biographic affairs, as well as his artistic and entrepreneurial activities. Today this material is scattered in the most varied of public and private places. Now this four hundred page volume presents the complete edition of the letters addressed and received by Titian between 1513 and 1576. Moreover, while the project was underway advertising activities for it were carried out. The publication was announced at the annual book fair in Frankfurt and at congresses pertinent to Titian studies, which were held primarily in Germany where studies on Titian are particularly advanced. As is well known, the first collection of Titian’s letters was built on the material gathered by Celso Fabbro and curated by Clemente Gandini for the Magnifica Comunità di Cadore in 1977 (reprinted until 1989). Until now, this has constituted the sole reference available to scholars. It was an undeniably a noteworthy publication, despite the necessity of acknowledging that it lacked correct transcriptions, comments to the texts and completeness. A new edition, in effect, has been wished for and recommended for some time now. This volume is the result, an achievement which engaged Puppi for the past five years and that also saw the produced the great exhibition Tiziano: L’ultimo atto (Belluno – Pieve di Cadore fall-winter 2007) and the edition on Titian’s life (1622) compiled by Tizianello. This volume not only expands the repertoire put together by Gandini by 80 new and previously unpublished letters but also identifies the location of letters that had been reported as lost and unrecoverable. The new edition is notable its detailed comments, which in the light of the latest Titian studies fully investigate and illuminate circumstances that had escaped the attention of specialists. New light is shed on the often tormented and difficult relationship between Titian and his patrons; from the Farnese circle to Philip II and the court of Spain as well as with close friends, starting with Pietro Aretino.

A Holding called Titian

The operations of the ateliers opened by the painter in Venice and in Augsburg were full of relatives and pupils who helped the Master

by Enrico Castelnuovo

Titian and workshop, Titian’s environment, Titian’s atelier, Titian and helpers. Our aim is to gain a better understanding of what certain terms mean and what lies behind the descriptions on the labels we read in museum galleries. We think we know: “Titian’s workshop” is a derogatory term; while clearly of Titian origin, the work does not display the qualities attributed to its author. “Titian and workshop” indicates that a painting is not entirely autographed, in other words it is a limiting if not lessening description. But does the integral autograph dear to connoisseurs and the market really exist? And is there one “Titian workshop” or rather were there more? The issue is not that simple and the book is quite important, not only because of the often previously unpublished information it presents on Titian’s various collaborators, but also because of what it narrates on the creation and operation of the “workshops”. The fact that it speaks of them in plural form is in and of itself a significant piece of information involving different times, spaces, people and aspects. Despite the Biri Grande house-atelier not far from the Fondamenta Nuove in Venice where Titian lived and worked for almost half a century, remaining constant the same, the workshop changed in appearance and composition. Let us begin from the most obvious aspect: the involvement of his family members. A rather common thing for artists, but particularly extended in Titian’s case: from his brother Francesco to his son Orazio, to his cousins Cesare and Marco, who died in 1611 almost forty years after the death of the Titian himself. The clan was composed of some extremely faithful relatives such as Girolamo Dente – not by chance known as Girolamo di Tiziano – and later Valerio Zuccate and Emanuel Amberger, son of the painter who Titian had met in Augsburg, while helpers, disciples and occasional collaborators succeeded each other for brief periods of time. The many foreigners included the Flemish von Calcar and Sustris, the Bavarian Hans Lielich and Christoph Schwars as well as the Greek El Greco. Another aspect is space: Titian’s travels to meet the Emperor in Augsburg in 1548 and in 1550-51 are in this sense particularly significant because it is here, as later in Madrid, that those that we may refer to as “virtual ateliers” were born: Titian workshops without Titian but instigated either by the passing-through and brief on-site activity of the artist or by the arrival of fundamental works of his, such as those created for Philip II and for El Escorial. He arrived in Augsburg with a number of collaborators, perhaps not “the seven mouths to feed” of which he speaks in a letter, but certainly three or four people of which he availed himself to help him both in the layout and in the replica of some particularly popular works. Here he also met local painters such as Christoph Amberger, who helped him restore the renowned Charles V at the Battle of Mühlberg from the damage it suffered during an accidental fall and whose son, Emanuel, would later become a faithful disciple and collaborator. Perhaps he also met Lucas Cranach, who had followed his patron, the Princeelector of Sassonia during his imprisonment. In Augsburg, in the Fugger houses and naturally at Biri Grande, Titian had a private “room” where he withdrew to paint, distinct from the large space of the atelier were all the collective work took place. The members of the workshops participated in the master’s work in various ways, both directly and indirectly. They completed barely sketched canvases and dressed them with “clothes and apparel”, replicated themes and compositions of successful work, and reproduced the most popular portraits such as those of pontiffs or sovereigns. They used or assembled composition formulae and schemes already tested in works destined to provinces near and far, such as the case of the very well-known Assumption of the Virgin at the Frari in Venice , the model of which was repeated in Dalmatia in the Dubrovnik polyptych and in the Lentiai one, in the Feltre area. The independent activities of his collaborators are significant and, in a way, revealing. Their works populated entire areas such as San Vito di Cadore, where the demand for paintings merged with problems of land annuities and titles. Here, the churches of San Vito, Venàs, Vinigo, Perarolo, Calalzo, Pieve and Nebbiù count works by Francesco, Orazio, Cesare and Marco Vecellio among their holdings. Painting for the Cadore communities was, however, a completely different thing to working for the orders commissioned by the Dominant body: the expectations, the customs and the paintings of Titian’s collaborators are here very different, often more archaised and less structured compared to those prepared for Venice. This is due to the desire to adapt to customs and wills different from those prevailing in the Laguna, as well as to the lack of a project that only Titian himself could conceive and oversee. The affirmation of Titian models in Europe is the result of a number of factors: the copious production of the workshop; the widespread diffusion through prints; and the exceptional authority of the models that continued to exert an inescapable lure through time and space. This impressive volume explains it, presents it, exemplifies it, with the aim of reinstating Titian’s entire operating system, an endeavour that implies long lengths of time and involves various authors. An important book that owes its achievement to Centro Studi Tiziano e Cadore, a praise-deserving institution, which amidst woods and peaks, manages to publish a periodical like Studi Tizianesch and conduct cultural initiatives that require a great deal of time and diligence.

(© Il Sole 24 ore 2010)

The Titian Firm

by Antonio Paolucci

When the young Titian painted his first frescoes at the basilica of Sant’Antonio in Padua with stories of the saint, the accounting documents recorded him as “depintor, or painter, one of the many who lent their work as esteemed artisans in the palaces and churches of Venice and the Dominion. We are in 1511. Sixty years later, in the etchings that propagated The Martyrdom of Saint Lawrence, a masterpiece of his old age, throughout Europe, Titian signed his name as “eques caesareus” or Knight of the Golden Spur. At that point, he was an imperial knight, a Count Palatine, who counted among his clients Emperor Charles V, the latter’s brother King Ferdinand, Maria of Hungary the regent of the Netherlands, Maximilian the king of Bohemia, the electors of the German Empire, the Roman pope, the powerful banker Anton Fugger, and the doge and the oligarchies of the Serenissima Republic of Venice. The painter from the mountain of Cadore, who had taken his first steps in the Venice of the old Bellini and the young Giorgione, had had in the course of sixty years a splendid career. He enjoyed the complete trust of Emperor Charles V and then his son Philip II. In 1547-1548 and then in 1550-1551 he was a guest of the Imperial Diet in Augsburg. His paintings were accessible in price only to the cream of Italy and of Europe. Titian was also extremely rich at the zenith of his fortune. He had astutely invested the earnings from his profession, multiplied his commercial and financial interests, run a real pictorial industry. Only Picasso’s golden old age can be compared to that of Titian. From the Biri Grande house-atelier in Venice – residence, workshop, display space and office all in one – the painter wove and ran a close network of international relations that we can call the “Titian system”. We find this definition – a synthesis of the great painter’s professional activities, critical fortune and market success during the 16th century – in a monumental volume curated by Giorgio Tagliaferro and Bernard Aikema, together with Matteo Mancini and Andrew John Martin. The volume is called Le botteghe di Tiziano (Florence, Alinari 24Ore, 2009, 270 pages, euro 90). It is correct to indicate them in their plural form because Vecellio’s models, his “factory of images”, have their main centres of production and distribution in the Venetion Biri Grande atelier and in the Augsburg one of the Imperial Diet. The workshops’ influence reverberated through European painting of international Mannerism with artists such as Lambert Sustris, Hans von Aachen, Hendrick Goltzius, Cornelis van Harlem, Jan Stephan van Calcar, and Anthonis Mor. But how did the “Titian system” actually work”? It worked thanks to an exceptional and extremely efficient production organisation founded on the involvement of students, relations, collaborators. For over half a century, like planets around their sun, crowds of painters of different origin, type and schooling revolved around Titian. Some were continuous collaborators, others only occasional. With the diffidence typical of mountain people, Titian trusted his family first and foremost, taken as a block of interests, like a business. Thus the name of his brother Francesco Vecellio, his son Orazio, his nephew Marco, and his cousin Cesare emerge over others. Names of known and recognisable artists stand together with them: Gian Paolo Pace, Girolamo Dente, and Polidoro da Lanciano. With many other collaborators it is impossible to arrive at the personal details. Carlo Ridolfi, a 17th-century Venetian historian, wrote that when Titian would go out, he would “deliberately leave the keys in the salon where he kept his valuables and, during his absence, his disciples would work on making copies of the nicest works, keeping one of each as spare”. Then, continued Ridolfi, upon his return to the studio, the master would finish them “by his hand”. Titian’s atelier was almost like an assembly chain that under the company trademark licensed paintings of different and often minimal degrees of autography. The “fine things”, those that most interested merchants and collectors, were the canvases of mythological-erotic nature and therefore, they were the most convenient to copy. How many nude Venuses, how many Danaë impregnated by the golden seed of Jupiter are there in Titian’s corpus! Some are entirely autographed, others only partially, and many in which Titian’s direct present drew close to zero. The idea that the “factory of images”, invented by Titian and spread throughout Europe from Madrid to Dubrovnik and Prague to the Flanders, was based on perfectly tested, efficient and flexible team-work is undoubtedly highly evocative. More than anything, it is true. On the other hand, in the past centuries, that is how the industry of figures was actually organised. Giorgio Vasari’s Lives has educated us towards a personal conception of artists’ activities. The romantic culture with the exaltation of the inimitable “genius” did the rest. This book by Giorgio Tagliaferro and Bernard Aikema allows us to understand the extraordinary importance of the atelier in the history of art. Titian’s case is exemplary. If his images of the ascended Virgin, flogged Christ, Venus, and Danaë captured Italy and Europe’s imagination, it is because a real “company” of pupils and copyists, who distributed those figure, perhaps reinterpreted or perhaps adapted them to the taste and figurative culture of the country of origin. This was certainly often the case of the foreign German and Flemish painters. If we examine the corpus of a great artist of the past (Raphael, Rubens, Rembrandt) in its entirety, we realise that it is the fruit of collective efforts, not of a sole solitary genius. We would not have the Raphael of the Vatican Loggia without Giulio Romano and Perino del Vaga, without Polidoro da Caravaggio and Giovanni da Udine without Machuca and Marcillat or without all the others who depicted the ideas of the Urbino-born painter. The frescoes on the Vatican Loggia were never directly touched by Rapahel’s brush. Yet, are the Doni portraits or the Madonna della Seggiola, a painting acknowledged as being totally autographed by him, touched by his brush? At the same time, we would not have Titian’s fortune, the acknowledgement of his central destiny in the history of the Venetian civilisation of colour, without the many artists who in different roles, at varying degrees of quality, in more or less engaging forms of involvement, contributed towards creating the corpus.

(©L’Osservatore Romano, 9 July 2010)